Note: we are accepting Anthology and Issue 09 submissions. Click Here to Submit

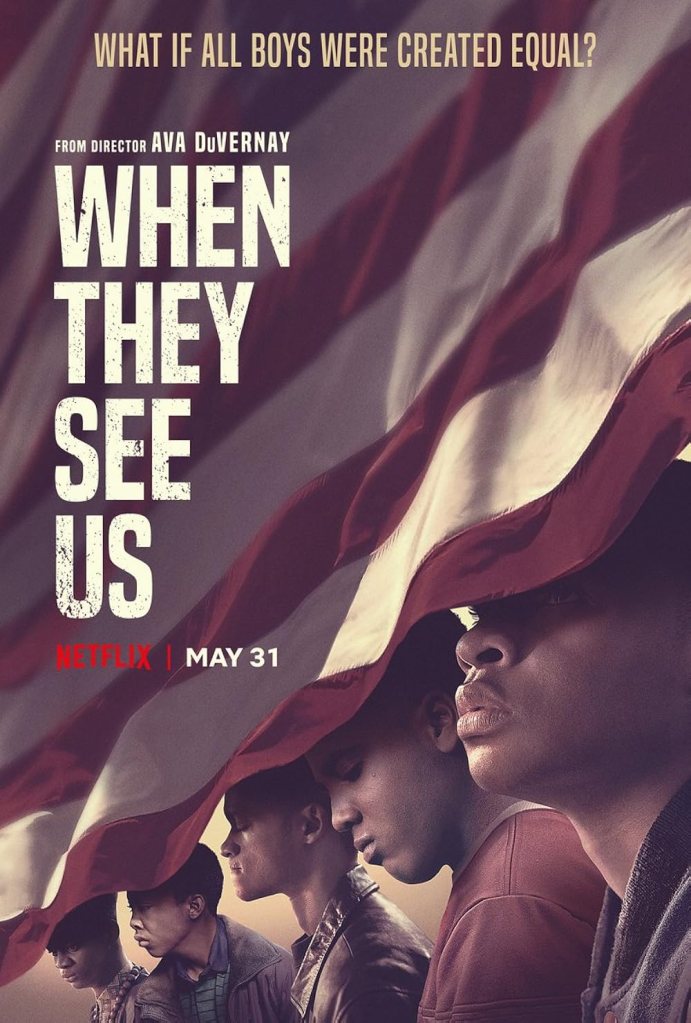

Often cinema poses as a vehicle for extensive political commentary. This reminds me of a quote by Michael Taussig on the submission of literary works into “the servile operation of getting them to say something that could be said otherwise”. But Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us is different. The 2019 miniseries does not become strained under the weight of politics to the point of overwhelming the audience. Instead, the series intentionally demands to be seen and heard quietly, beside the frames of identity politics and racial violence.

When They See Us largely echoes the statement (though clichéd but significant): “Justice delayed is justice denied”. The series explores the lives of Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, and Korey Wise. The brutal assault of a white woman named Trisha Meili is discovered, and these five teenage boys are accused of the crime. From the beginning, the police are somehow absolutely convinced of their involvement. However, the lack of any sort of evidence points to the obvious politics being played behind such an accusation. It is not the act they never committed but the mere attribution of their race, of being black, that holds them convicted in the court for the crime of assaulting a white woman. One of the characters (the mother of one of the boys) dishearteningly wonders—What even is black?

But the spectres of the past certainly haunt the present. Following their release, life outside of prison gets difficult for them. Once being incarcerated means, irrespective of whether you actually committed the crime or not, as fittingly remarked in the series, “they are counting on you going back in” (One of them does return to prison). This eerily echoes the mechanism of power exercised at the level of life as noted by Michel Foucault. Precisely: “a power to foster life

or disallow it to the point of death”. They are continuously being watched and their life is continuously disciplined through various methods by the power structures. At its core, then, the series captures police brutality, institutional violence, and systemic racism, all of which are intensely inherent within the judicial system.

Get Issue 08 (Digital & Print Version) Click Here

It is remarkable the way DuVernay weaves the notion of truth into the storyline. From the moment these boys are detained by the police till the end of their trial, they are being obsessively coerced into confessing to the crimes they never committed in the first place. It is quite shocking to witness the conviction in which the police, the legal system, and the people unanimously believe in this narrative. The discourses of truth produced by the system of law have a certain notion of truthfulness attached to its structures. Hence, the quickness with which we believe in the narratives of the state. There is a certain conviction in the eyes of the prosecutor, Linda Fairstein, in the series. It is this gaze of certainty (the scholar and author, Lisa Stevenson, calls this a stately gaze) that prevents one from thinking about alternative ways of seeing the narratives of truth generated by the structures of law. It is this gaze that prevents them from asking at least once about who could be the real culprit. It begs the question: how do we resist the stately gaze of certainty? How do we move towards ethical ways of seeing the marginalized community of people? The seemingly juridical system of law, posing to serve and protect the citizens, becomes only a facade.

About the Reviewer:

Thamanna is a researcher and a writer based in Kerala. Her love for the perfectly placed commas and words in a sentence drives her editorial impulse and appreciation for the language. She also enjoys reading stimulating conversations on books, cinema and art.

Leave a comment