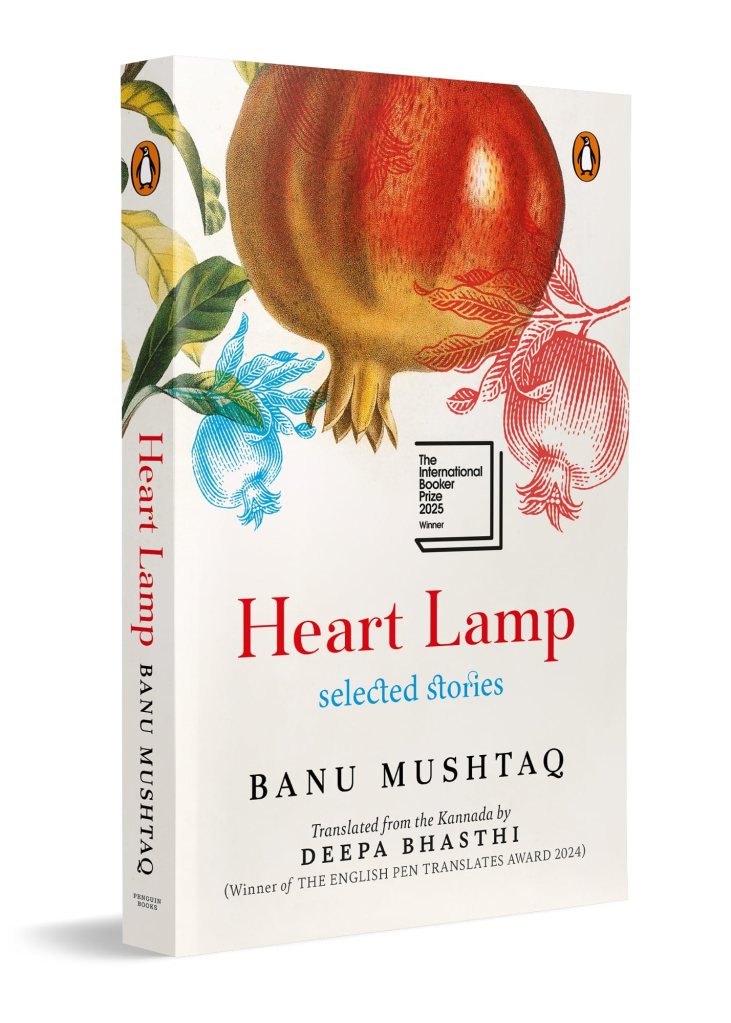

Even now, evening chai conversations at home are reserved exclusively for my mother. As she restlessly forages through the stories of hardships about marriages and dreadful pregnancies (she became a mother for the fifth time at the age of 46), I listen. Even as she persistently insists on me to get married and have children, I listen. She can never seem to converse about her hardships alone. It has to be balanced with letting me know the importance or necessity of marriage and having children. For women, it is never easy to walk out and flush away these ideas instilled in them by the system of patriarchy. Picking up Banu Mushtaq’s ‘Heart Lamp‘ reminded me of these conversations.

This book is a collection of twelve short stories. Mushtaq writes about women and how the institutions and social structures of society, politics, religion, and family oppress them. The stories speak about systems of beliefs that are favorable for a man but critical of a woman. If the story “Fire Rain” is about a mutawalli going to lengths for the justice of a rotten corpse of a Muslim man, accidentally buried in a Hindu cemetery (ironically, in the end, it is revealed that it was indeed not the corpse of the man that they thought were buried), but unaware and unbothered of his own son being hospitalized, another story, “Black Cobras”, is about a drunk and womanising husband eager to marry another woman because his wife couldn’t bear him a son. Yet another story, named “Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal” narrates a tale about a man proclaiming grand gestures of love for his wife but also burdening her with seven pregnancies. One cannot help but think about Robert Browning’s My Last Duchess, a similar tale about control disguised as love.

Note: we are accepting Anthology and Issue 09 submissions. Click Here to Submit

Mushtaq’s stories are part of the literary tradition that emerged in Kannada, the Bandaya Sahitya Movement. Deepa Bhasthi, the translator of this book, notes down that Bandaya means “dissent, rebellion, protest, resistance to authority, revolution and its adjacent ideas”. In that sense, each story in this book echoes a voice of resistance. Resistance comes in different forms in the novel. For instance, in some of the stories, we can see women walking out of these systems that subordinate them. Or in some other, we can hear whispers amongst women indicating their own skepticism for the rules and laws laid down by the patriarchal system: “They say that those who get an operation done to stop getting pregnant will not reach jannat. Is that true, Aashraf?”. There are many instances in the book that subtly knit and speak about the unspoken injustice suffered by the women. (I use the knitting metaphor purposely as it might remind readers familiar with Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and her idea of womanism). Mushtaq creates such spaces inhabited by women, where they can contemplate and critique patriarchy without the controlling gaze of men. To emphasize this more, the last story in this book is called “Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord!”. Herein, the woman is literally beseeching the lord to “not be like an inexperienced potter” the next time if he were to build the world again, to create males and females again”.

The premises of the stories in this book are solid and grounded in our everyday realities. Mushtaq is careful not to be outrightly political to the extent of overwhelming the readers. However, some stories ended way too abruptly, and I was left wondering if I would read these stories again. I sat with this thought, and perhaps I might not, as the collection did not give me that craving to look back and think about these stories.

About the Reviewer:

Thamanna is a researcher and a writer based in Kerala. Her love for the perfectly placed commas and words in a sentence drives her editorial impulse and appreciation for the language. She also enjoys reading stimulating conversations on books, cinema and art.

Get Issue 08 (Digital & Print Version) Click Here

Leave a comment