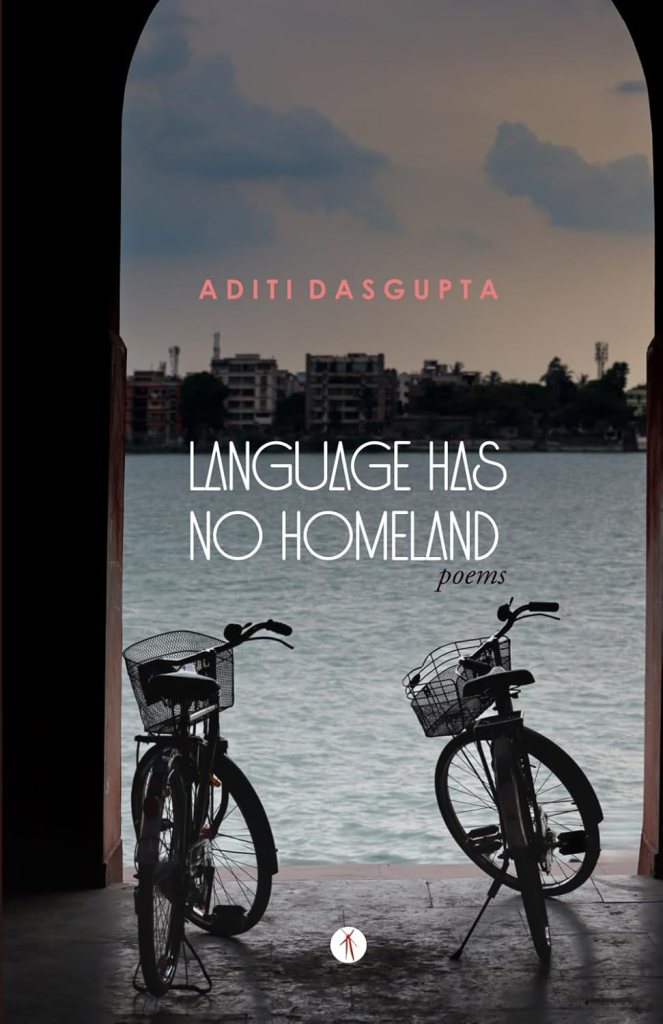

Aditi Dasgupta’s Language Has No Homeland is not merely a collection of poems – it is a multilingual act of remembering, resisting, and returning. It is remarkable for how it transforms multilingual-everyday-life into poetry that is quite intimate, political, and deeply textured.

Using multiple tongues as varied as Urdu, Bengali, Tamil, Assamese, Konkani, Sanskrit, Bodo, Kashmiri, and more – Dasgupta’s work refuses to treat languages as fences. Instead, she lets them braid into each other, creating a complex and interconnected web of experiences, where identity is fluid, inherited, borrowed, and sometimes invented.

A Book Rooted in Multitudes

The author makes the collection feel intimate where every poem feels like a memory softened at the edges, shaped by migration, domestic rituals, and the small rebellions of everyday life.

Across the book, the poet lets spoken textures – kitchen idioms, childhood mistakes, festival chants, the sounds of mothers and grandmothers – become the architecture of identity. Whether it’s the child begging for mishti doi before the bhog (“eyes like roshogolla” in Mishti Doi), the Konkani tenderness of a grandmother calling someone “Gomman,” or the Tamil ache of “Oodal in the Time of Kozhukattai”, the poems transform regionality into universality.

Where Translation Becomes Emotion

Dasgupta asserts that translation often “resist complete fidelity”not out of ignorance, but because infidelity is the nature of language itself in the book’s Preface. A unique strength of the book lies in its refusal of linguistic purity. Dasgupta’s perspective spans multiple languages, yet remains universal enough for anyone regardless of a different cultural background or mother tongue to connect with. This naturally gives the poems a hybrid voice – a voice that mirrors the way many of us think : in blended tongues, in borrowed phrases, in untranslatable feelings.

Thematic Depth: Childhood, Womanhood, Borders, Loss

The collection is divided into Innocence and Experience. Childhood appears in poems like Budbud, where a boy makes bubbles out of a Limca bottle, or Haathekhori, where first alphabets on a sun-warmed slate feel like “a moyna fluttering into view.”

Womanhood, particularly the invisible labour, defiance, and tenderness of women emerges with force. Poems like Jhajhraa portray a woman “frayed from devotion” yet expected to return refreshed and less tired each morning.

Migration and memory echo through Pind and Ashchi, where departures never feel final and home is always plural.

And the poems confronting illness, death, and ritual – Thanimai, Antyesti, Biri leave the reader with a quiet devastation.

INNOCENCE: Poems to sit with

1. Tita

Tita is a tender portrait of childhood resistance – that tiny, universal battle between a mother insisting on “bitterness first” and a child negotiating for sweetness. Subarna’s distaste for the charred tita (bitter gourd) becomes symbolic of how children imagine life: stories must begin with river and hero, not with hardship. The mother’s firm wisdom that even the “sweetest river carries a little tita” turns the poem into a gentle lesson in emotional resilience. Dasgupta captures the exchange with humour, warmth, and an understanding of how love often hides itself in discipline.

2. Pagutharivu

A quiet but powerful rebellion unfolds in Pagutharivu. The young boy, Kavin, faces an exam paper he is not prepared for, and the poem maps the exact moment when fear mutates into reasoning – pagutharivu – the courage to make his own choice, even if it is the “wrong” one. Dasgupta juxtaposes his trembling pen with his father’s Darwinian precision and his mother’s temple offering, showing how expectations crowd a child’s world. Yet the poem ends with a small fire in his chest: the birth of reasoning not as defiance, but as selfhood. It’s one of the collection’s most quietly political poems.

3. Pind

Pind is a moving reflection on displacement and the fragile geography of memory. Through the eyes of a young girl who crosses a border she barely understands, Dasgupta writes a poem steeped in loss: the missing blue cupboard, the wrong-shaped room she tries to sketch, the roof that doesn’t echo rain as it used to. Her new home loves her, but the love is “wrapped in another dialect.” The poem’s strength lies in its simplicity – the ache of a childhood interrupted by migration, and the idea that a pind is never just a place, but a version of ourselves we leave behind.

EXPERIENCE : Poems that stay with you

1. Nidar

Nidar is a stark and visceral poem about a girl walking home alone at night – fearless in posture, yet shadowed by the constant threat that women learn to navigate from adolescence. Every detail breathes realism: the keys clenched like a weapon, a scooter slowing down, breaths stitched back into the chest once safety is reached. Dasgupta captures the exhausting choreography of self-protection. The poem becomes both a tribute to women’s vigilance and a critique of a world that demands such vigilance in the first place.

2. Nine Yards of Zidd

A generational arc of womanhood is woven into Nine Yards of Zidd. The sari, first inherited as freedom, slowly becomes a garment of expectations – “pressed beneath the iron of approval,” its borders policing her body, movement, and breath. The author’s imagery is striking : the choreography of pleats, the instructions barked like rules, the moment of rupture when she simply lets the pleats fall. In that single act, zidd (stubborn resolve) is reclaimed. The poem is a powerful feminist statement about reclaiming choice from rituals meant to contain it.

3. Antyesti

In Antyesti, the poet enters the rituals surrounding death with a gaze that is tender, unhurried, and unflinchingly honest. From the pandit’s turmeric lines to neighbours performing silent chores, the poem observes grief not through spectacle but through the small, communal gestures that accompany loss. The most striking insight arrives at the end: the ashes that merge with the soil return to the grain that eventually feeds the living, making nourishment itself a form of antyesti. It’s a profound reframing of mortality, collapsing ritual, ecology, and human continuity into one.

Aditi Dasgupta’s Language of Resistance

Language Has No Homeland is a luminous, textured, and deeply human collection. It is for readers who love poetry that blends cultures without apology, who understand the ache of belonging to many places and none completely, who find themselves thinking in interlinear scripts. Dasgupta’s voice is tender yet sharp, playful yet philosophical and above all, necessary.

Perhaps the most compelling phrase in her Preface is “goal… to highlight the language of resistance”. Dasgupta’s resistance is subtle but far-reaching: it lies in refusing singular identities, in reclaiming domestic narratives, in archiving overlooked voices, and in accepting that language itself rebels against boundaries.

SUBMISSION OPEN for Fiction Writing Contest. Win Cash Prizes and Dual Publication with The Hemlock Journal and Remington Review. Click Here to Know More.

About the Author

An ordinary feminist, a storyteller, and a researcher at heart are the words that define Aditi. An MPhil scholar in English literature from Jamia Millia Islamia, India, her intellectual inquiries have consistently focussed on and engaged with postcolonial traumas in Indian literatures in English. She completed a Diploma in Translation and Creative Writing program at Ahmedabad University. Aditi is an IWL (Institute for World Literatures, Harvard) alumnus and completed a residential program at Yale University to understand the nuances of modern storytelling. Apart from that, she has authored Silencing of the Sirens, which has been critically acclaimed in literary circles in India.

About the Reviewer

Archana Ramakrishnan is a writer, reviewer and researcher based in India. She enjoys exploring stories through movies, and books while staying curious about pop culture, literature, and art. Reading and writing helps me grow mindfully, expand my horizons, embrace new perspectives, and appreciate diverse cultures, fueling both my creativity and my passion for learning.

Leave a comment