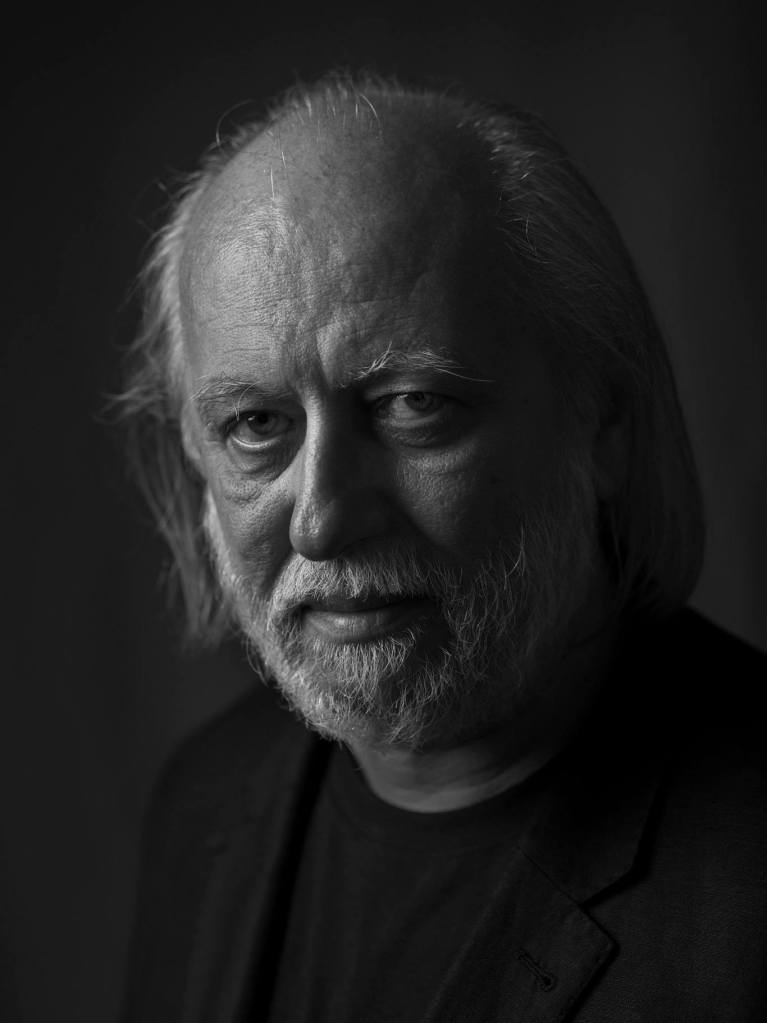

On 9 October 2025, the Swedish Academy announced that the Nobel Prize in Literature had been awarded to Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai, in recognition of a body of work described as “compelling and visionary, which, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art.” The choice has prompted renewed interest in a writer long admired by a devoted readership but less well known to general readers. For those encountering Krasznahorkai for the first time, his novels can feel like strange, shining altars to despair and hope, intensely lyrical, and deeply unsettling and to be read with an insane effort.

A Glimpse of the Man Behind the Prose

Born in Gyula, Hungary in 1954, Krasznahorkai came of literary age in a country shaped by political upheaval, loss, and cultural crossroads. His writing belongs to a Central European tradition that draws on Kafka, Thomas Bernhard, the grotesque and absurd, yet also reaches out towards East China and Japan in particular in search of states of stillness and rupture, as quoted by him: “My life is a permanent correction”.

Krasznahorkai’s signature style is bold, extraordinarily long, winding sentences, often paragraphs without a full stop, that spiral outward in layered deviations and internal monologues. As the Nobel committee put it, his “flowing structure of the language with long, winding sentences devoid of full stops” is now a hallmark of his voice, making his books termed ‘rare currency’.

His Nobel Prize feels both surprising and right – a quiet victory for a writer who never sought fame but stayed true to his vision. Through books like War and War, Melancholy, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, and Seiobo There Below, he writes of collapse and endurance, of how art and language survive even when everything else fails. His worlds are dark, but they shine with a strange light, the one that reminds us that meaning can still exist amid ruin. For someone who avoids attention and rarely speaks, Krasznahorkai has created work that speaks for all who watch the world with both sorrow and wonder.

In the author’s own words, upon receiving news of the Nobel win, he said:

“This award proves that literature exists in itself, beyond various non-literary expectations, and that it is still being read. … For those who read it, it offers a certain hope that beauty, nobility, and the sublime still exist for their own sake.”

This statement, humble yet deep, reveals a constant theme in his writing – tension between the ideal world of art and the stubborn reality we live in.

Milestones & Acclaimed Works

While Krasznahorkai has published many works over the decades, a few have stood out as landmarks, both critically and culturally:

Satantango (1985) is often considered his breakthrough, with readers still remembering it as it left a lasting impact on them. Set in a bleak Hungarian collective farm, it tracks the unraveling of collapse and betrayal in a remote village, with a fluid structure of narratives of illusion, power, decay, and hope.

The Melancholy of Resistance (1989) (often translated from Hungarian – Az ellenállás melankóliája) explores revolt and collective delirium, set in a small town besieged by a mysterious circus.

Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming and Seiobo There Below are other notable works that expand his thematic and stylistic range, incorporating broader geographical and spiritual concerns.

While Sátántangó and Melancholy are more famous, László Krasznahorkai’s War & War is one of the fan favourites with people still praising the prose of the book. The story is about a suicidal clerk and an antique manuscript, with intriguing imagination and words weaving both beauty and horror in one place.

His more recent work, such as A Mountain to the North (2023) and his 2024 novel Zsömle odavan, continue experimenting with satire, heritage, and mythic dislocations.

Over his career, Krasznahorkai has garnered awards such as the International Booker Prize (2015) and the U.S. National Book Award for Translated Literature (2019), long before the Nobel.

Why His Work Resonates Today

Today, when we’re dealing with climate worries, unstable politics, and an existential crisis, Krasznahorkai’s bleak worlds don’t seem imaginary anymore, they feel real and urgent, like they were written for this moment. The Nobel citation’s phrase “in the midst of apocalyptic terror” is not hyperbole as many of his fictions dwell in the zone where the world is collapsing, yet still demands meaning.

Krasznahorkai’s writing doesn’t offer quick comfort or happy endings. But that’s exactly where its strength lies. He reminds us that even when words feel heavy or difficult, language can still hold beauty, resistance, and grief all at once. In his world, despair isn’t a victory, it’s a kind of watchfulness, a way of staying awake to what’s happening. The light in his stories may fade, but it never disappears completely.

He often writes about destruction and renewal, illusion and hopelessness, and the fight of one person against forces too large to control. These themes go beyond Hungary or Europe; they speak to everyone, everywhere. Reading Krasznahorkai is like testing how far fiction can go, how stories can help us make sense of a world that often feels like it’s falling apart.

Anecdotes, Quotes & Moments of Grace

One anecdote often retold in literary circles is about Krasznahorkai’s approach to travel. He has made pilgrimages to Japan and China, seeking not only cultural inspiration but ways of seeing stillness amid trajectory. Those visits shaped the tonal shifts in his later works, where meditation and apocalypse often stand in counterpoint.

An often repeated quote (in translation) by the author (paraphrased) is:

“I do not write to escape the world; I write because the world will not let me go.”

Another thought-provoking line from The Melancholy of Resistance describes the landscape of collapse:

“The town was a constellation of graves lit by the soft glow of ruin.”

These lines show how Krasznahorkai’s writing explores inner emotions just as deeply as the world around his characters.

Final Thoughts

László Krasznahorkai’s Nobel Prize is not just an honour for Hungarian literature, it’s a reminder that stories still have the power to survive even when the world feels like it’s falling apart. His writing can be intense, wide-ranging, sad, and restless, but never lazy or comfortable (being infamous for his never ending syntax). For readers who are ready to be challenged, his sentences are long and winding as they offer comfort in chaos and a strange kind of hope amid disorder.

If you’re starting out, begin with Satantango, then move to The Melancholy of Resistance. Follow that with War and War, a haunting novel about a man who wants to preserve a mysterious manuscript before the world ends. After that, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming and Seiobo There Below will show you the full extent of his imagination and on how he stretches art, language, and storytelling to their limits in a time that often forgets their value.

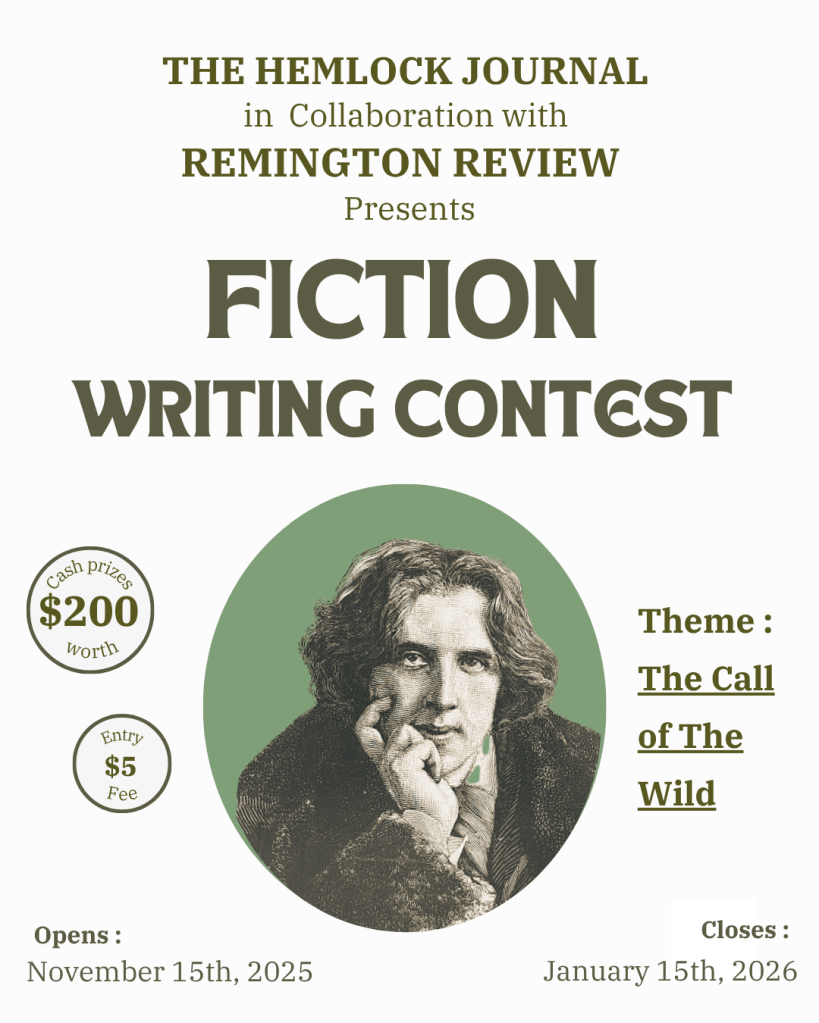

SUBMISSION OPEN for Fiction Writing Contest. Win Cash Prizes and Dual Publication with The Hemlock Journal and Remington Review. Click Here to Know More.

Written By: Archana Ramakrishnan

Archana Ramakrishnan is a writer, reviewer and researcher based in India. She enjoys exploring stories through movies, and books while staying curious about pop culture, literature, and art. Reading and writing helps me grow mindfully, expand my horizons, embrace new perspectives, and appreciate diverse cultures, fueling both my creativity and my passion for learning.

Leave a comment