‘When the flower blooms, the bees come uninvited.’

~Ramakrishna

The road was held together with flocks of goats and serpentine curves. Thirty cents had bought us an hour and a half of coiled vertigo. The bus driver threw in the bananas for free, and finally dropped us at the bottom of a hill, just past the sign. Population 507 Souls.

Surrounded by glaciers and razor-thin waterfalls on three sides, the town spread out like the leaf of a pipal tree, unfolded on the slope of Han peak. We hoisted our packs and began the long climb to the imposing medieval citadel cantilevered off the cliff above us, effortlessly hanging in the morning Himalayan air. We passed a whitewashed barn, decorated with rows of circular cow patties stuck on its walls- fuel, furnishing, and function. The white-uniformed brown servant who met us at the top was named Madhukar. He told us that he spoke only Hindi. In perfect English.

“Is this Naggar Castle?” Julie asked. Head bobble.

On the other side of Naggar River, in the 13th century, a powerful ruler with a reputation for cupidity and stupidity, had built and fortified his royal residence of Gardhak. On the advice of his wazir, Rana Bhosal had also buried his own queen along the watercourse, to ensure a continuous supply of irrigation for his rice fields. She had been alive at the time of her presumed reluctant interment, but clearly not a favorite of the wazir. In 1460 AD the Raja Sidh Singh, had the stones from Rana Bhosal’s palace passed hand to hand, through a chain of human laborers across the river to the current site of Naggar Castle. His view of the Valley of the Gods and snow-laden peaks was still staggering.

When the Chinese pilgrim monk Xuanzang came through the surrounding mountain passes in 635 A.D., his route followed a series of meditation caves, into a fertile valley of gold and silver, and red copper and crystal lenses. He entered a green idyll of twenty Buddhist monasteries, fifteen Hindu temples, and mixed devotees who lived together in harmony.

Madhukar showed us to our rooms- gigantic rooms with adze-carved ceiling beams, sloping floors, priceless Victorian furniture, gingerbread beds, and a verandah with red scalloped Mughal-curve carved portals, projecting wooden brackets, and one of the most spectacular panoramas in the world.

In the attached dining room, a large antique glass chandelier hung pendulously over a huge oaken table, surrounded, on the wallpaper, by a herd of gazelle head trophies. A fireplace sat in one corner of the room and in another, Alan and Adera, two Kiwi hikers who, although exuberantly friendly towards us, didn’t seem to have much to say to each other. We arranged to meet them later for dinner.

Julie wandered off to check out the new neighborhood, and Robyn and I stretched out over our gingerbread bed, and a quiet game of Scrabble. It was all so absurdly romantic.

He came in through the window on a triple word score. Robyn and I looked at each other. The intruder spoke.

“A very good afternoon, Sahib.” He said. “Perhaps you may be wishing to purchase some ganja?” We looked at each other again. The balcony was suspended in space, several thousand feet above the valley floor. In harmony, our interloper levitated imperceptibly above the sloping floor.

“It is only of the very highest quality.” He assured us. It seemed credible. I asked him how he got up here, to the side of the castle suspended in the air. He only giggled, and head bobbled, and giggled again. I looked back at Robyn and reached into my Kashmiri pouch. A commodity like that, it just doesn’t float through the window every day. He left through the dining room, counting his rupees.

Madhukar, his white uniform a little worse for the day, was already serving Alan and Adera, when we finally entered the dining room around seven thirty. They had spent the afternoon summiting most of the peaks around the valley, but we had climbed higher. Both groups had healthy appetites for Madhukar’s dhal and rice and veg curry. Halfway through the trifle, the chandelier began to swing. Everyone looked up from the custard. I looked to Madhukar.

“Is that an earthquake?” Robyn asked. Head bobble.

“Are we safe?” Asked Julie. Head bobble.

“Does this happen very often?” Alan inquired. Head bobble.

“Jesus, man, say something. Are we in danger?” I asked. Everyone was keenly aware that we were hanging off a cliff, conspicuous in the extreme to the unforgiving gravitational forces of the planet. Madhukar’s lips finally moved, in English.

“No problem.” He bobbled. “Naggar Castle five hundred years old. Many earthquakes. Naggar town flattened.” He moved his hand across the scene, palm down. “But Naggar Castle, no problem.”

I learned much later how right he was. And why. There had been a mighty and disastrous earthquake in 1905. Naggar town was destroyed. Naggar Castle didn’t move. The reason lay in its local architectural construction style, an antiseismic technique known as kathkooni. Stone layers were punctuated with long pieces of cut wood, ensuring a lot of resilience in the structure. It rose, to be topped by a grey slate roof. But it never fell.

The wooden carvings in its walls were no less exquisite than the wooden carvings within its walls. Every evening, the temple bells around Naggar tolled the music of compassion, peace and brotherhood, unrestrained. Later, tucked in our gingerbread beds, we watched the shooting stars, through the Mughal holes in the verandah.

* * *

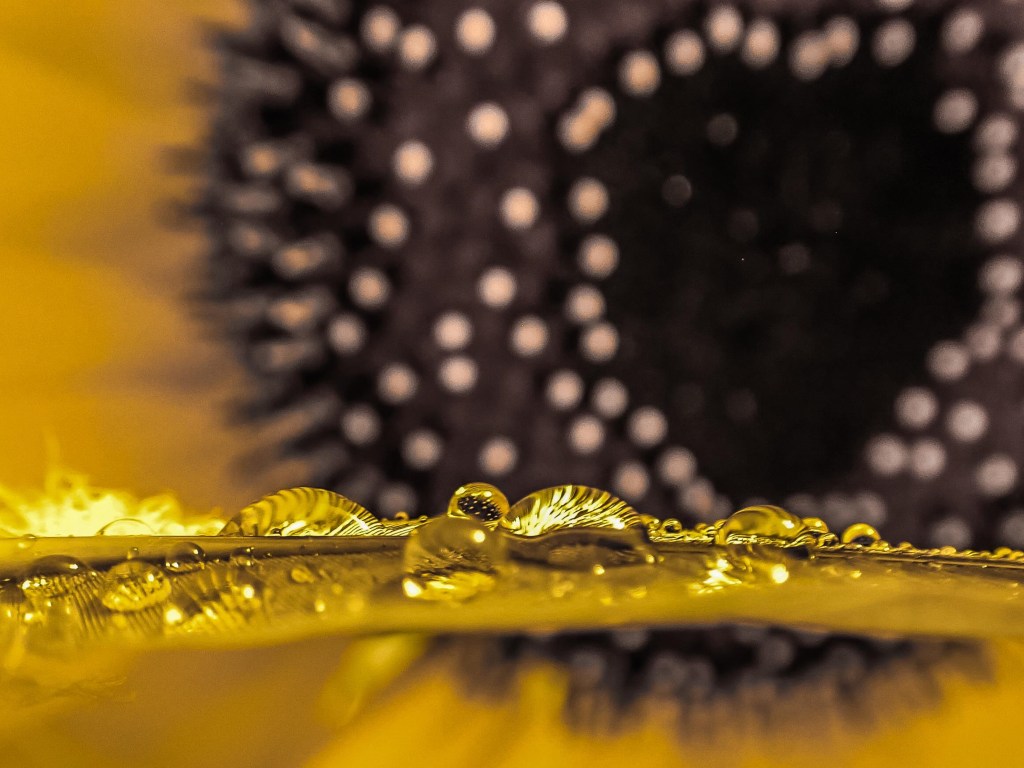

The spicy incense coming from the small temple in the courtyard, wafted over our breakfast next morning. Vermilion paste smeared the doorway. I asked Madhukar what it signified. He told us of the powerful legend that was associated with the castle, and the tiny Jagti Patt temple within its walls. There was a massive stone slab, five feet by eight feet and six inches thick, inside the shrine. When the gods decided to make Naggar the celestial seat of all the gods in the world, they transformed themselves into honeybees, endowed with Herculean power. They flew to the high sacred mountain of Deo Tibba, cut a monolith from its face, and flew it back to its present site in the castle courtyard. It is still the unshaken belief of the locals that, even now in times of calamity, all the Kullu gods assemble here to mitigate the suffering of the people.

The three little girls playing in the mud below the castle didn’t sound like they were suffering, if the giggling that came through the mud was accurate. They sang a song behind our descent. A devotee of the courtyard temple ran ahead of us, with a dab of the doorway vermilion paste smeared on his forehead, marking the bond between the wild god honeybees and the humanity below. We passed the grey sandstone 11th century Shiva temple of Gauri Shankar, carved with monkeys and lions and flowers, and topped with an umbrella-like slate roof.

At the bottom of the hill was a makeshift A-frame bakery, and its shorthaired Tibetan owner, in his saffron shirt and a carnelian chuba, draped loosely over two great high boots. His dog didn’t bark, as it came out of the darkened interior of the shack, to check the sudden traffic. Julie and I looked at each other, in a simultaneous recognition that this could be an answer to our problem.

Robyn was about to have her 29th birthday, but it was going to be at Naggar, and it was going to be the next day. I had already asked Madhukar about a birthday cake, but he told me it was impossible. One of the differences between the Tibetans and the Indians, it is that the Tibetans will expect that nothing is possible and go on to disprove it; whereas the Indians will expect that nothing is impossible and go on to disprove it. When an Indian tells you that something is impossible, go see the Tibetan. Julie whispered to him that we would return next morning, without Robyn.

But that day we hiked up another height, to the Light of the Morning Star, Urusvati, the Institute of Himalayan Studies founded by Nicholas Roerich. Russian mystic, painter, philosopher, scientist, writer, traveler, and public figure, Roerich was the kind of man who would have been ignored if he had stayed at home. By escaping to live in another culture, he became noteworthy and unique, because of the noteworthy and unique geographical displacement, dislocation, and dissonance. His breathtaking mansion, with a resplendent view of the Dhauladhar Mountains on all three sides, was adequate reward for his gallery of mediocre paintings. Roerich is widely credited to have formulated the principal difference between culture and civilization. I hadn’t realized there had ever been one. However, in one of the rooms I met Jackie, a thirty odd, very odd, fanatical feminist, who was living proof that one can exist without either.

This encounter was counterbalanced at dinner that evening by a new addition to our Naggar nucleus. Francois was a delightful balding research mathematician, originally from Paris, and working in Bombay. He told us that Peter O’Toole was on his way to the Wild Bee Castle, to film a movie version of Kipling’s Kim. Madhukar said that he had heard it as well, and that nothing was impossible. Unfortunately, or fortunately, Peter O’Toole didn’t arrive until a month later. He played a Tibetan monk, with absurd doddering mannerisms, and an atrociously inauthentic costume. It may have been just as well we left early.

There was nothing inauthentic about our Tibetan baker next morning. Julie and I snuck out while Robyn was still sleeping. We let Alan and Adera and Francois know about the birthday party later and dropped the two hundred meters to the bakery entrance. His dog licked my hand as we drank ginger chai, and Julie drew a picture of a birthday cake. He didn’t seem to understand at first, until she added the candles. We had seen the convergence of culture and civilization. Or so we thought. We arranged for him to personally deliver the cake up the hill that evening, all for ten rupees.

The day melted into Scrabble games, a brief entourage of Indian tourists from Bombay, and planning for my true Destiny.

Madhukar’s curried veg repast was up to his usual standard of unexceptional sustenance, but he returned to the dining room in a slightly excited state, carrying rice and a message. Someone was at the door for Julie. Robyn wondered out loud who it could be, but stayed to continue the conversation we were involved with. Julie got up quietly, to engage the convergence of culture and civilization. She wasn’t quiet long.

“What?!” was heard all over the valley. “What?!” she screamed again. I jumped up, motioning to everyone seated that they should remain so, and that everything was under control. Reaching the kitchen door, I saw the source of Julie’s exclamation.

Our Tibetan baker had arrived with his creation, three very heavy loaves of dung-like bread, clearly inspired by the barn wall pattern of cow patties in his universe. Goodness knows what he thought the candles were.

“Big balep, no?” He asked sheepishly.

“No!” Julie said. But it was too late. The birthday moment had arrived, and we had, as our only substrate to create a facsimile of a birthday cake, three loaves of ponderous hefty Tibetan barley bread. We turned to Madhukar, recently arrived back in the kitchen. No head bobble. Bad sign. We thanked the baker and sent him back to his cultural roots. Without drawing breath, we turned to the rest of the kitchen, rummaging through shelves and drawers, looking for a means of salvation. There wasn’t much, but there was enough.

We found a tin of custard powder, a jar of Bhutanese red jam of some unidentified fruit, and bananas. Julie sliced the balep breads across their horizontal galactic axis, creating six dense thinner layers from three lead weights. I spread the Bhutanese jam on each side of the millstones. Just another brush with Paradise. Madhukar, meanwhile, had fired up the stove and already had a pot of daffodil camouflage custard ready to pour on our assembly. All of us attacked the bananas with knives, until the yellow molten mass was covered in sliced cadmium coins. A large white wax candle stake was driven through its heart. It looked, for all the world, like a birthday cake.

Jules and I sported it into the dining room on a refrain of Happy Birthday. From the pain in my arms, a forklift would have made for a safer workplace. Or a godswarm of wild honeybees, endowed with Herculean power.

Robyn smiled and thanked us and broke the first knife in the ritual cutting of the replica. We all eventually got a piece and tucked in with the kind of enthusiasm that all civilized birthdays demand. I looked back at the carnage at the end of the evening, as Madhukar was switching off the chandelier. The bananas and custard were gone. In their place were several wedges of baked barley flour. None of them had teeth marks. With the cone geometry of what was left, you could have completely reconstructed three large loaves of Tibetan bread. It was September 11th.

Ten years earlier, they had finished building the World Trade Center in New York. They had used the wrong materials. Here, in the Castle of the Wild Bees, they had the architectural construction expertise required, to withstand all the mighty and disastrous earthquakes of life.

(Non-Fiction from The Hemlock’s Issue 6, Winter 2024)

About the Author

Lawrence Winkler is a retired physician, traveler, and natural philosopher. His métier has morphed from medicine to manuscript. He lives with Robyn on Vancouver Island and in New Zealand, tending their gardens and vineyards, and dreams. His writings have previously been published in The Montreal Review and many other literary journals. His books can be found online at http://www.lawrencewinkler.com.

Leave a comment