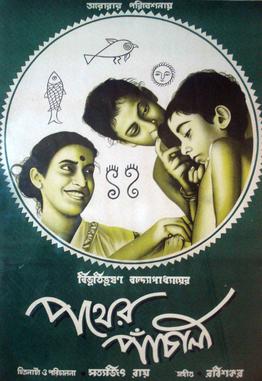

When Mainak Bhaumik decided to take up Apu and Durga as the names of the two protagonists, for his 2018 Bengali film — Generation Ami, he knew that the fate of his characters were sealed from the very beginning. Such a decision would inevitably impact the way in which the audiences ( a majority of whom were Bengalis) would look at his film. A very probable first impression would be something like — “oh it must be another pretentious modern adaptation that will totally ruin the essence of the original film!” And when that particular film is made by a movie maestro like Satyajit Ray, the task of an adaptation becomes all the more challenging. After all, Ray’s exceptional cinematic oeuvre is not just a matter of universal pride for the Bengali community, it is also one of the many ways in which Bengalis all across the globe have time and again, defined and described themselves to the rest of the world, thereby playing a crucial role in shaping their cultural identities. Thus, it was very likely that Bhaumik’s decision to experiment with one of the most renowned works of such a monumental man would earn him more sneers than praises. And still, against all odds, Generation Ami managed to strike a familiar chord with its audience. While it certainly did not break any box-office records or become an overnight blockbuster, Generation Ami told a story so close to home that it instantly resonated with today’s youth. This article attempts to explore the many ways in which Bhaumik has managed to revisit and re-imagine the nuances of Satyajit Ray’s classic film – Pather Panchali within the context of an urban contemporary Bengali middle-class milieu. Primarily assessing the characterization of the two protagonists — Apu and Durga in both the films, this paper provides a comparative analysis of the two films, shedding light on their structural and thematic similarities, which ultimately stands in testament to the profound universality of human experience in spite of all its complex subjectivities.

The unforgettable siblings’ bond — Apu and Durga

On being asked if the characters in Generation Ami share any resemblance with those from Ray’s Pather Panchali, Mainak Bhaumik said in an interview :

“The names Apu and Durga are very common in Bengal. Durga is a tomboy and it is she who pushes her brother to do things. So it transferred me to Bibhuthibhushan’s novel which was later made into “Pather Panchali”. I wanted to pick timeless characters, so I ended up selecting these names.”

Generation Ami does not claim to re-tell the story of Pather Panchali. Rather, it takes inspiration from Ray’s heart-warming depiction of the unconditional love and bonding between the two siblings — Durga (Uma Dasgupta) and Apu (Subir Banerjee) to portray in his own film, the unexpected connection that develops between the two main characters — Durga (Sauraseni Maitra) and Apu (Rwitobroto Mukherjee).

The setting, time period and socio-economic contexts of both the films could not be more different from each other. Pather Panchali takes us into the fictitious village of Nischindipur — an idyllic hamlet located somewhere in rural Bengal, where want and suffering is rampant, luxury is rare and poverty can be found everywhere. Yet, amidst such an environment of abject struggle and hardship, the everyday life of Durga and Apu is never shown to be devoid of joy. Durga loves Apu unconditionally, and they cherish each other’s company, managing to find happiness in the littlest of pleasures that life has to offer — from taking her younger brother to the faraway fields to catch the sight of a train to them chasing the local sweet-seller, in the hope of getting candies they can hardly afford — Durga and Apu’s unforgettable bond is at the heart of Ray’s film.

In Generation Ami, we come across a spatio-temporal backdrop that is in stark contrast to what we had previously seen in Pather Panchali. Yet, the selfless, compassionate bond shared between Durga and Apu, forms the very crux of the film. Unlike Ray’s film, here we see that Durga is not Apu’s own sister, but a cousin from Delhi, who comes to live with Apu and his family temporarily. This slight yet far from insignificant deviation, perfectly fits into the more modern, contemporary mould of the film — it shows how in the rapidly changing times that we live in- real, genuine human connections can be formed beyond the mere ties of blood. It is therefore not a matter of coincidence, that a lonely yet defiant soul like Durga finds her true feeling of “home” in a place far away from home — she finally finds in her cousin Apu and his family, the love and comfort that she has been desperately searching for in her own parents.

In an article published by Woke Waves Magazine, Nina Kessler states that :

“In a survey conducted by the Family Equality Council, findings revealed that over 77% of Gen Z individuals believe that the definition of family goes beyond blood relations or legal bindings, a stark contrast to earlier generations. This suggests a shift towards valuing emotional bonds and supportive networks, regardless of the traditional familial ties.”

Thus, the concept of a “chosen family” is epitomized in the beautiful bond that Durga forms with her cousin, Apu. Her constant reminder to her young brother — “Haal chherona bondhu”/ “Don’t give up, my friend”, becomes an essential life motto for Apu, although, as we get to know by the end of the film, it is an advice that Durga, quite ironically, could not apply to her own circumstances. The wisdom and practical insight that Durga imparts in the very limited time that she spends with Apu is enough to leave an indelible mark on the young boy, motivating him to come out of his shell and speak up , daring to live life on his own terms.

Material Poverty v/s Emotional Poverty

While Ray’s Durga, dies in the arms of her beloved mother Sarbajaya, with the spirit of her mother’s tough love helplessly attempting to save the ailing girl, till her very last breath, Bhaumik’s Durga, on the other hand, doesn’t even get to have that comfort — she dies in awful want of that motherly love and affection that she had been craving and chasing, all throughout her life. Hailing from a broken family, Durga’s parents are on the verge of divorce. Both of them are working professionals who are way too busy in their own lives to notice that their only daughter has become a tortured scapegoat stuck in between their conjugal battle of egos. Durga eventually falls into clinical depression and even attempts to take her own life . Dismissing their daughter’s tormented condition as a mere cry for attention — following Durga’s first failed suicide attempt, Durga’s parents decide to send their daughter away to Kolkata, for further medical treatment, and to also avoid the judgemental eyes of the other people(especially the other Bengali families) in the vicinity. By taking inspiration from Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, Bhaumik’s film not only illuminates the unbreakable sibling bond as a predominant motif capturing the essence of real human connection in the face of hardship, but it also manages to shed light on the challenges imposed by society and how it has changed over the years. If in the pre-independent society of rural Bengal, physical poverty and extreme neglect bring about the death of Durga in Pather Panchali, then in the case of Generation Ami, it is emotional poverty that ultimately drives Durga to the path of suicide.

A term coined by Dr. Ruby Payne, the concept of ‘emotional poverty’ describes a “lack of emotional resources, such as the capacity to self-regulate, form trusting relationships, and process emotional experiences. These deficits do not emerge in a vacuum but are deeply rooted in systemic inequities, adverse childhood experiences and environmental stressors.”

In Bhaumik’s Durga, we see a clear case of emotional poverty — owing to her experiences of growing up in an emotionally unavailable household, Durga never learnt how to regulate her emotions properly, and thus, even when her parents managed to provide her with all kinds of material comfort, she was inherently deprived of emotional stability. Such is the way of life that both film-makers capture so subtly in their respective stories — While a Durga in Satyajit Ray’s world, would have to die out of untreated ailness, simply being a tragic victim to a malignant fate brought about by extreme poverty and destitution, in Mainak Bhaumik’s world, Durga’s suffering is more emotional than material or physical — her death is portrayed as an immediate result of not any bodily suffering, but of years of emotional abuse. If in Ray’s world, death comes and snatches away all the light and life from a young Durga who, until her very last breath, is brimming with life, then in Bhaumik’s world, it is Durga herself who chooses death; she willingly surrenders herself to oblivion for it seems to her, as the only feasible option - the only means by which she can escape the agonizing cycle of pain and mental suffering that has been slowly crushing her spirit, until all that exists of her is a lifeless, soul-less body made of flesh and bones. Disappointed and disowned by all those people who mattered to her, Durga, much like Willy Loman from Arthur Miller’s Death Of A Salesman, realises that she would perhaps be valued more in death than in life. And ironically, that is exactly what happens. It is only when she dies that her parents come to see her — while they had forgotten to wish her on her birthday, they are eventually forced to remember her on her funeral.

Apu’s parents — the emotionally distant father and the overcompensating, sacrificial mother

Turning away from the simplicities of pre-colonial rural Bengal, Mainak Bhaumik’s story delves deep into the complexities of life in the 21st century, as it follows the journey of an urban middle-class family, living in the heart of Kolkata. While they are definitely not “poor” in the way one might characterize the family of Harihar Ray in Pather Panchali to be, Bhaumik makes sure to give us an immersive insight into the struggles that Apu’s father (played to perfection by Shantilal Mukherjee) has to undergo in order to do justice to his overwhelming responsibility of being the sole breadwinner and provider in a family of four. (five, if we count the momentary, yet far from trivial presence of Durga). Clearly downtrodden by the weight of his professional duties and familial responsibilities, Apu’s father is the prototypical middle class salesman, brimming with a false sense of pride, who has been recently demoted in his office — an information which, along with the fact that he occasionally enjoys alcohol or cigarettes in order to calm his nerves — remains a secret that he hides from the rest of his family — simply because, even the slightest expression of weakness or vulnerability would be seen as unacceptable, by a man like him. We also find out as the film progresses, that just like Apu, his father too, in the heydays of his youth, was an aspiring musician. A dreamer just like his son, Apu’s father, however, is forced to sacrifice his dreams, in the pursuit of a stable future.

While hailing from two absolutely different backgrounds, the character of Apu’s father in both Ray and Bhaumik’s films, much in contrast to what immediately meets the eye, actually has a lot in common. Both these fathers, at their very core, are people who genuinely love and care for their families, and yet fall short of finding a suitable way to express this love. They have in some way, both as husband and father, disappointed their families. In the case of Harihar, we come across an almost fatally optimistic man — a priest who can barely make ends meet, and yet dreams of making it big as a writer. When all the doors to a stable future close in on Harihar, he takes the decision to step out of the village and head off to the city in order to explore newer opportunities. Leaving his poor family behind for an indefinite period of time, Harihar fails to communicate with his family at a time when they need him the most . When he finally does return, it is clearly too late, as he realises that he has lost his daughter forever without even getting the chance to say goodbye for one last time. Such is the complexity of life — in the pursuit of economic stability, we often end up sacrificing things that should have mattered the most.

Cut to Mainak Bhaumik’s film, where Apu’s father is no soft optimist, but a harsh, almost cruel realist who after having discovered his son’s hidden passion for writing songs in the corners of his chemistry notebook, does not miss the chance to taunt him saying —

“Kobi hobe, gaan likhbe, shei gaan bajare bikri hobe? shei takay shongshar cholbe?” / “you want to be a poet…you want to write songs…you think those songs would ever sell? You think you can run a house, take care of a family, just by writing songs?” The father in Mainak Bhaumik’s film has been forced to adopt almost a pseudo-practical approach to life, curbing all capacity to appreciate creativity or artistic talent.

Both Ray and Bhaumik portray the character of Apu’s father as an emotionally distant figure. In fact, their emotional unavailability can be directly connected to their physical unavailability. Both the characters have jobs that require them to stay out of their own houses for a long, often indefinite period of time. Closely related to this common connecting factor of the emotionally distant father is the presence of a constantly nagging, overtly sacrificial mother, whose desperate attempts to make up for the absence of the father often become a cause of suffocation for the children. In Pather Panchali, Sarbojaya is portrayed as a woman with an indomitable spirit. A mother who is tough on the outside but soft from the inside, Sarbojaya doesn’t dream too big — she just hopes that both of her children are well fed regularly, that her son, Apu gets proper education and her daughter, Durga can be married off to a respectable family. We hardly ever see her expressing a desire of her own, all her personal dreams and desires have been obliterated, almost unconsciously, ever since she got married — and so, even when she naggingly complains to her husband about their insufficient financial conditions, she does so not out of concern for her own wellbeing, but because she simply wants her children to lead a happy, comfortable life, free from sorrows and misery. In a crucial moment of the film, Sarbojaya tells her husband- “tumi jokhon thakona, shotti buker bhetor ta kemon jeno kore…eshob toh tumi bujhbena…khachho, dachho, nijer taal ey acho, maine pachho ki pachhona…”/ “when you are not around, I feel an inexplicable sense of discomfort bottling inside me…but you wouldn’t understand these things…you live without a care, eat, sleep and go about without really worrying about whether or not you made money…”

This scene finds a wonderful parallel in Bhaumik’s film, where we see Apu’s mom (once again, impeccably played by Aparajita Addya) also complaining to her husband about her everyday worries stating — ”Ei je masher moddhe eto din kore bayre thako, tumi aar ki bujhbe amar tension”./ “Every month, you stay away from home, for so many days…what would you know about my situation.”

In both cases, we witness the picture of a struggling father who refuses to really express his emotions and a dotting mother who is just physically, emotionally and mentally exhausted and dragged to a marginal position. Neither of them can truly understand or empathize with the other person’s situation. Both Ray and Bhaumik show the picture of a family where the parents inhabit a world of complex individual needs, societal demands and psychological pressures that are not just different, but also quite incompatible with the imaginative, innocent world of youth inhabited by Durga and Apu.

“Loke ki bolbe? ”— The age old taboo

Pather Panchali and Generation Ami might depict two completely unique worlds that differ in terms of place, time and other cultural and socio-economic factors, but it is interesting to note that much of the conflict shown in both the films, arise out of that one infamously common and universal “loke ki bolbe /what will people say?” factor. Social acceptance and reputation are crucial elements that characterize the Indian society. In an article published in The Brown Girl Magazine, Ryan Gaur writes about the Indian populations’ obsession with social reputation.

Tracing this back to the time of British colonization of India, Gaur writes about how the British colonizers’ nefarious policy of “divide and rule” resulted in the development of long-term hostility and self-doubt among the Indian communities , which continued to linger on, years after the Britishers left our country :

“Inventing the façade of unworthiness amongst Indian communities allowed the British to manipulate them…Internalizations this strong did not disappear when India gained independence and was split in half. This may have created more animosity amongst brown-skinned people in South Asia, further propagating the wave of spirit breaking British ideals.”

In Pather Panchali, we see how caste and class interact in the context of the Indian society, thereby shaping the complex social hierarchy. A Brahmin priest like Harihar might struggle to earn a decent salary, but when offered work by a man of a lower caste, his caste pride stops him from accepting the offer. Even when he fails to make ends meet, he still dreams about inviting the other villagers to celebrate his newborn son’s “annaprashan”, just because- “loker kache maan ta thakbe”/ “we will retain society’s respect”. This theme of social reputation becomes all the more pronounced in Mainak Bhaumik’s film.

In Generation Ami, Durga’s parents care so much about the opinions of others that they choose to isolate their daughter by sending her away to Kolkata, after her failed suicide attempt. In one of Durga’s recollections of her life back in Delhi to Apu, Durga remembers how, after being molested by a family member as a child, she was forced by her mom to stay silent, in order to avoid society’s judgements. Even after getting divorced, her parents try their best to maintain the façade of a “happy family” in front of others, just to protect their social reputation. After Durga’s final suicide, Apu has a direct confrontation with his father where he says- “chhele meye ke janona, shomoy ta ki jache janona, kikore bachte hoy shetao janona…shudhu ektai jinish jano loke ki bolbe…chhele meye ra ki bolte cheyeche ekbaro shunte cheyecho”. / “You don’t know anything about your children. You don’t know anything about the times we live in. In fact, you don’t even know how to live. All you know is ‘what would others say?’ Have you ever wondered what your children want to say?”

In the heated exchange that follows between father and son, the latter finally expresses all the pent-up rage, while calling out their hypocrisies and double standards in parenting , reminding his parents that their dream of seeing their son excel in studies, pursue science and get admission in an IIT, is nothing but an attempt to be flattered in the eyes of the society.

Mainak Bhaumik’s modern re-telling of Satyajit Ray’s classic, thus explicates certain universal elements of human life and experience, that remains timeless to all. In their realistic depiction of a society lapped in its own vices and prejudices, both Ray and Bhaumik manage to communicate the value of having genuine human connections in an otherwise pathetic life of sordid sufferings. While a bed-ridden Durga on her deathbed makes the solemn promise to take her brother to see the train in Ray’s film, in Bhaumik’s film we see the modern, more matured version of Durga — who irrespective of the inner battles she fights every day, still manages to support her cousin Apu, in every way possible. From gifting him his first guitar to organizing a secret party with his friends at home, Durga, much like her original namesake, manages to be the beaming ray of light in the life of a boy with a lot of dreams. And so in the success stories of all the Apus, there lies the crucial, undeniable contribution of a Durga, whose radiant presence lingers around, even in the darkness of her absence.

(A creative non-fiction piece)

About the Writer

Adreeja Majumder is a postgraduate student of English Literature at the St. Xavier’s College Autonomous, Kolkata. She is a digital content creator and a budding writer with a penchant for experimenting with different styles ranging from poetry, fiction and non-fiction.

Leave a comment